Dialectical Sculptures

The subjects of the pictures in this set might be regarded as either beautiful or ugly, or both. Their identity not only questions this distinction, but also that differentiating sculpture from structure, and explores the relationship between these binaries. Further, the photographic depiction, with its focus on depth of field and apparent three-dimensionality, challenges the assumption of the “flat” in photography with this rendition of the sculptural.

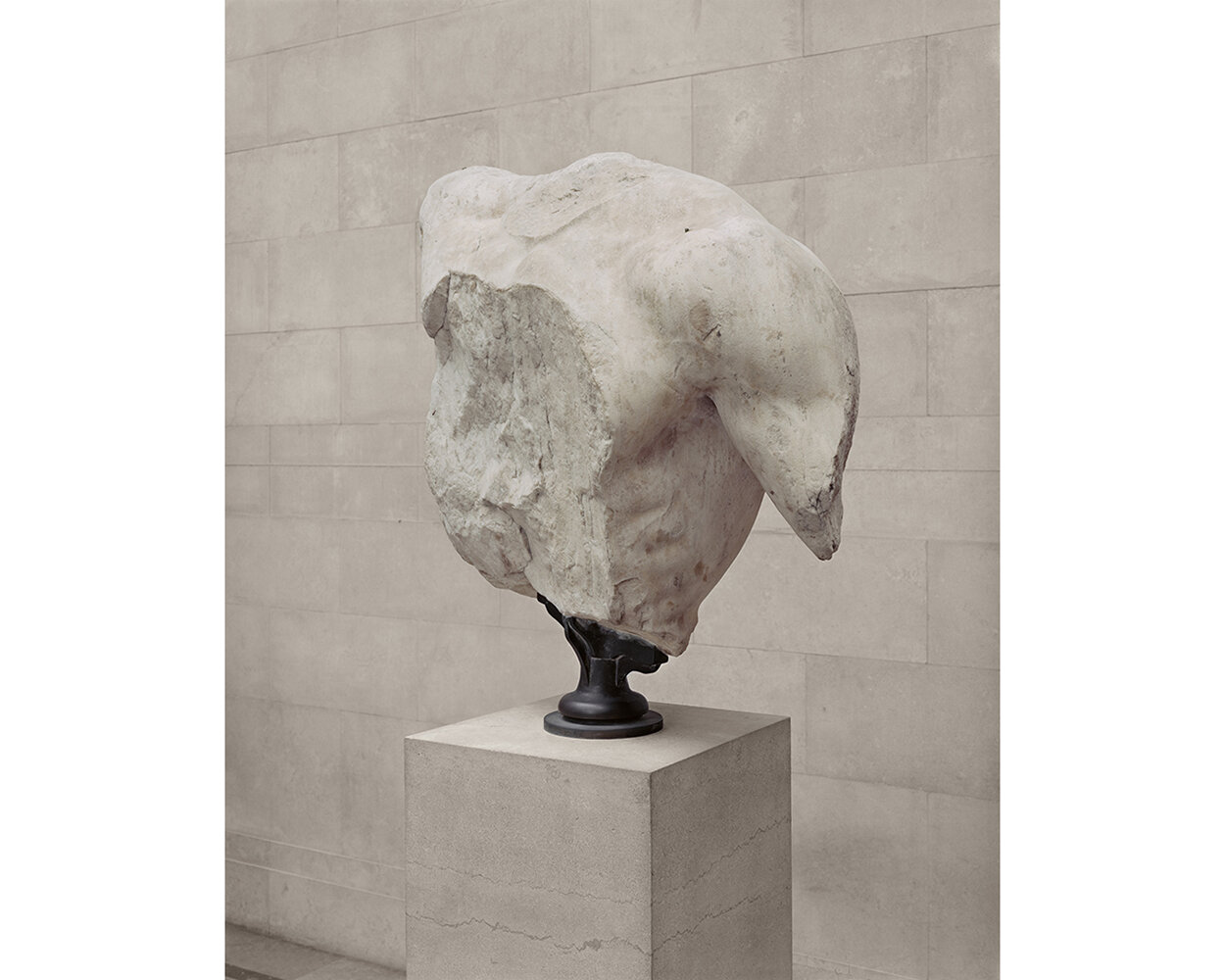

The Parthenon sculptures are simultaneously a work of art exemplifying the height of Western Classical sculpture, and embodiments of the butchered victims of war. They are also the products of colonial looting and the spoils of cultural reappropriation. Venerated for their artistic and cultural legacy, in Britain they were scrubbed and chiselled clean and white to conform to Neoclassical conventions, imposing an extraneous normativeness upon them. In consequence, the body of Hermes looks flayed, and their current temple is a temple to Western culture.

The 400 kV air-blast circuit breakers are live and were photographed at the closest proximity possible. Any closer and they would kill you. As with the photographs of the Parthenon sculptures, these are the most detailed large format photographs of these objects made to date. National Grid granted permission on condition that their location remains unidentified. These structures were designed by electrical engineers without any artistic considerations and have as much business being in an art gallery or museum as a religious statue.

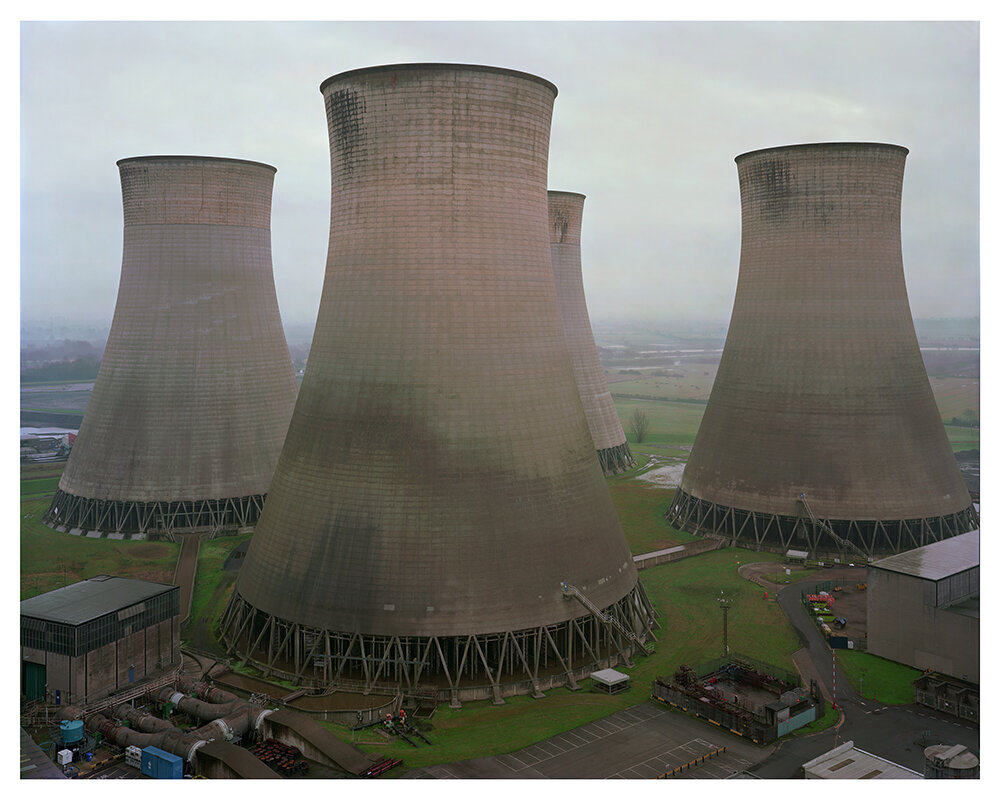

The hyperboloid natural draught cooling towers are perfect exemplars of form follows function. These structures stand 115 meters high, 90 meters wide at the base, and yet their reinforced concrete is less than 18 cm deep; the ratio of shell diameter to wall thickness is less than that of an egg. They are what Bernd and Hilla Becher call “nomadic” architecture; once their industrial use ends, they are demolished. Long regarded as the iconic industrial structure in the landscape, within a decade or two, they will all be gone. As will the coal burning power stations that they served. Cooling towers are both benign recyclers of water and accessories to global warming. But their grace and magnitude are astonishing, and in these tableau photographs, their aging concrete skin and smooth contours are presented in forensic attention to detail and sculptural depth.

The four electrical panels are part of a 1930s railway control room. The front of these panels depicts discrete sections of track, schematically presented in an Art Deco style. This façade was created by industrial designers, whereas the obverse was produced by electrical engineers. One was functionally aesthetic, the other functionally industrial. Long decommissioned, when it was operational, the back of these control panels, a live electrical installation, would have been kept safely behind closed doors. Practical access was the primary criterion in the design and configuration of the back of these electrical control panels; presentation was not an issue.

The sandstone Brimham Rocks were largely shaped in the Devensian period, when their forms were carved by the forces of glacial action, gelifluction, water erosion and weathering. In the 18th and 19th centuries there was a belief that they were the work of Druids. Many more millennia of weathering, plus a couple of centuries of tourism, have further whittled their contours. Barbara Hepworth and Henry Moore, among others, have taken inspiration from these geological sculptures.

The “Riparian Sculptures” are part of an ongoing series photographed by the banks of the Thames. The coal jetty pillars at Beckton are all that remain of what was once the largest gas works in the work, and the jetty at Greenwich Power Station is a remnant of its original reliance on coal. These late 19th century and early 20th century structures have aged into obsolescence as their technology and role have outlived their function. The patina of their senescence has morphed what was once emblematic of industrial might into a peaceful stasis of industrial antiquity. The passage of time is manifest in chronological duality - the century-old cracking and flaking of industrial coatings alongside the daily twofold tides presented in photography’s here and now of the past.

“Scrap” is both brutal and subtle. Awaiting recycling in a London scrapyard, the discarded girders are piled up with other heavy lumps of metal. Their filthy chaos is juxtaposed by the colours and textures of their forms. Photographed from a distance of only a few yards, precariously close, almost ungrounded, as though the mass might collapse and engulf the viewer, who is confronted, via sight, with the smell and feel of the metals. These are today’s yesterdays, the Monday morning from our ruins of the future.

Together, these series of pictures befit a dialectical approach. They question the nature of beauty and the criteria for veneration; the difference between sculptures and structures; the presumptions placed on the interpretations of photography; and the formal expectations and properties that photography is assumed to possess. Each is replete with contradictions. All too often the polemics forced onto photography masks its ambiguities, refusing to acknowledge its innate polarities by assuming a single lobby. This set intends to disrupt this reception by challenging various assumptions, including the unquestioning assertion of the “flat”. Each of the subjects in the series is photographed in such a way to enhance the sculptural sense of depth in the picture, contesting the presumption of the “flat” by pushing the possibilities of focal depth to create a picture with an apparently three-dimensional appearance. Such is the intensity of the photographic gaze, details and facets are exposed anew. The tableau size, substance, and nature of these works of art engenders an engagement without preordained interpretation; rather, they constitute a contradictory experience awaiting an undetermined reception.